Implementing the Cybersecurity Act of 2015: A Public-Private Specifications Approach

Arguably the most significant cybersecurity development of 2015 was a stunner. On Friday, 18 December 2015 – with everyone leaving on the holidays – the U.S. Congress unexpectedly passed the Cybersecurity Act of 2015 and it was immediately signed by the President. It became the organic law of the United States, including far reaching amendments to the Homeland Security Act of 2002. In the process, it established a new information sharing paradigm for threat intelligence and defensive measures, created a new architecture around the NCCIC (National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center), revamped Federal Agency roles, and provided a rather large carrot on a stick for the private sector in the form of essentially blanket immunity for getting on board.

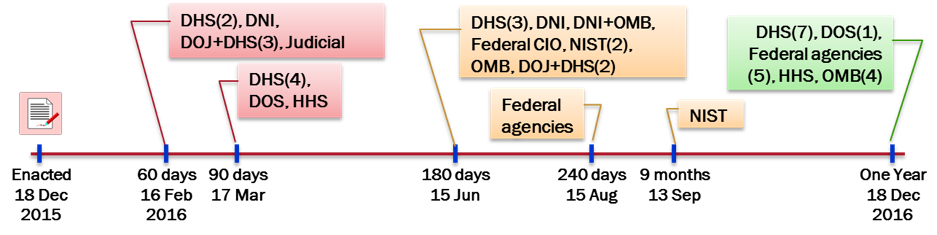

In addition to all the adopted changes, Congress decided it would hold the various responsible agencies accountable through an almost impossibly tight schedule for 65 deliverables and reports directly to the legislators. Forty-four are required during the first year, and first set of 7 occur at 60 days on 16 Feb 2016.

As everyone arrives back to work in 2016, the impact of what occurred on 18 December is just becoming to be realized. It is also begging for an answer to the key question of how on 16 February “the Director of National Intelligence, in consultation with the heads of the [DOD, DHS, and DOJ], shall submit to Congress the procedures required” to implement the capabilities demanded by the Act.

A Public-Private Specifications Approach

This is not the first time that Congress was faced with a need to establish real-time information sharing capabilities with network service providers. Although we are dealing here with voluntary cybersecurity capabilities, the need two decades ago to assist law enforcement authorities executing judicial search warrants for network forensics led to the enactment of CALEA – the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 1994. CALEA provided a means for the government to execute a court order requesting network operators to isolate the forensics of specified user perpetrating a crime.

The diverse and constantly array of telecommunication and information technology, however, presented a challenge for government. Congress’ approach was innovative and flexible. They empowered the Attorney General to develop and publish the information sharing interface requirements between government authorities and the providers. Any industry standards body or vendor could then develop technical specifications or implementations that met those requirements and assert sufficiency to obtain “safe harbour” under the law. That sufficiency could be challenged by the Attorney General if she believed otherwise. If a challenge occurred, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) served in a kind of third party judicial capacity.

Similarly, the growing need for the availability of electronic evidence in civil litigation led the Federal judiciary collectively – with Congressional approval – to adopt a new rule for eDiscovery including what was effectively a mandate for private sector development of flexible request-response specifications. This resulted in an Electronic Discovery Reference Model.

It is also worth noting that there are other precedents for such an approach that have existed within the DOD public-private world such as the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) Security Technical Implementation Guides (STIGs).

These kinds of public-private approaches for technical interfaces for sharing information have worked relatively well over many years. It could be used now by the agencies responsible for implementing the Section 103 provisions of the Cybersecurity Act of 2015. An extensive set of slides on the “deconstructed” requirements underlying the Act can be found on the OASIS Cyber Threat Intelligence Technical Committee site.

So how would this play out over the coming weeks? The DNI together with DHS, DOD, and DOJ are faced with the essentially impossible task of providing definitive specifications for implementing the required capabilities by 16 February. Indeed, given the multiplicity of rapidly evolving and constantly changing specifications for sharing information on cyber security threats and defensive measures, definitive specifications for doing so doesn’t make much sense. See, for example, the OASIS CTI specifications for the acquisition and sharing of cyber threat intelligence, and for defense measures, the CIS Critical Security Controls that have been adopted globally.

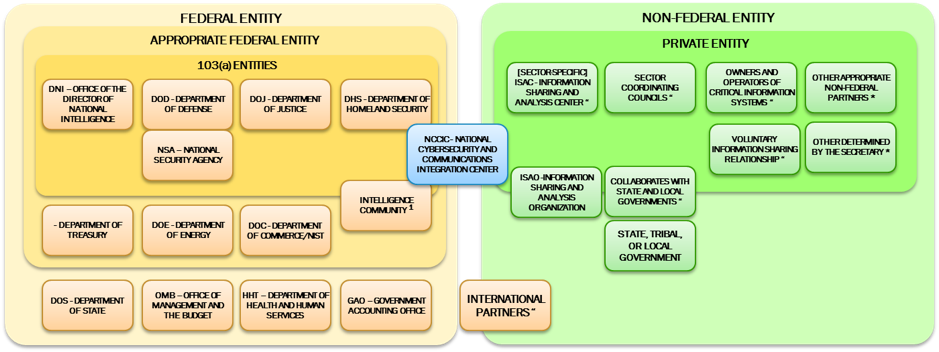

What the DNI could do, however, is present a plan where it would publish generic requirements for the information sharing interfaces, coupled with an additional requirement that the asserting standards groups, vendors, or even other agencies demonstrate consistency with those generic requirements to DHS or DOD. This action could also be coupled with extensive proactive outreach to groups presently engaged in producing specifications and other capabilities for effective dealing with cyber security threats and defensive measures. Indeed, the composite of the Cybersecurity Act and its changes to the Homeland Security Act, results is an extremely diverse array of identified entities all engaged with the NCCIC, as shown below. There is simply no “one size fits all” here, and leveraging the creative energies, innovation, and responsive capabilities of the private sector to meet public sector requirements, seems like the best way forward in implementing the Cybersecurity Act.